After my 15-day epic Xinjiang trip, spent hiking and sweating and traipsing all around the largest province in all of China, one would think that the next logical step would be to come back home to Shanghai to rest, relax, and recuperate before heading out on another trip. One would certainly think that, perhaps, but one would clearly never have been traveling with me.

After one day home to do laundry and repack my bag, I headed back to the airport on my own to embark on my next (and final, due to a new rise in outbreak travel restrictions) trip of the summer of 2021: one week camping and horseback riding up in the grasslands of ᠥᠪᠥᠷᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯᠥᠪᠡᠷᠲᠡᠭᠨᠵᠠᠰᠠᠬᠤᠣᠷᠣᠨ (Өвөр Монгол) Inner Mongolia 内蒙古. NOW, before I go on further, a pause to look at some cool language stuff. First, as always, when I’m including names of places I visit, I want to include the words in a variety of languages: English (because this is the language I and, I can only assume, most of you who are reading this can easily read and understand), Mandarin (or, “Chinese” — see early blogs for more on this but there are so many different Chinese languages that are used throughout the country; Mandarin is the language based out of Beijing and now widely recognized as the “official” language of China/this is the dialect taught in schools/this is another one of those “buy me a drink in person and we can chat more about it offline” topics…), and whatever the prominent local/minority dialect is (for example: Kazakh, Uyghur, Tibetan, etc.). As I’ve mentioned before, I think it is important to share both the local and national names for these places I’m traveling to. Especially in a country like this. And in times like these. For offline conversation reasons. SO, in Inner Mongolia, the majority of the population are Han (again, what you think of when you think “Chinese”), Mongol, and Manchu, so I will share all of the names (or as many as I can find online) in both Mongolian and Mandarin.

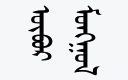

Here’s the thing about the Mongolian language: it is written vertically. When Genghis Khan united the Mongols, he found scribes to transcribe what had only been a spoken language up until then into a written script – they made modifications to traditional Uyghur script and flipped everything vertically, reading from top to bottom, left to right. Similar to cursive, everything is connected without breaks. So, “Inner Mongolia” written in the Mongolian language looks like… well… the picture you see just below this paragraph. When I tried to copy and paste the text, it could only process the information horizontally (as you can see in my paragraph above). But… that’s not correct. Now, if we are to take that (down below) text and shift it into Cyrillic script — the alphabet used by many Slavic and Turkic languages including Russian, Bulgarian, Czech, Ukrainian, and many more — it would look like Өвөр Монгол. Which probably still doesn’t help a majority of you with being able to sound it out, so let’s take it a step further and shift that from the Cyrillic to the Romanized version, using an alphabet you are likely to be more familiar with: Öbür Mongγul, or Övör Mongol.

Permit me one more quick language paragraph (how could you NOT find this fascinating?!) to do the same thing to the Mandarin. First, let’s look at the Mandarin for Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region: 内蒙古自治区. (Technically, this is the Simplified Chinese version of it. We could get real fancy and go look at the Traditional Chinese, but for today, Simplified Chinese is what is used in Mainland China, so that’s what we’ll stick with.) Unless you can read Mandarin, those characters aren’t really giving you any clues on how to read or speak those words. So, let’s shift this into Pinyin, or the Romanized version of Mandarin written in an alphabet we can make sense of: nèi měng gǔ zì zhì qū. Or, to try to help our eyes make sense of it even more: Nèi Měnggǔ Zìzhìqū. The first three characters loosely translate to “inside ancient Mongolia” (Inner Mongolia) and the second three to “since rule area” which, when combined, mean “autonomous region.” LANGUAGE IS SO COOL. WORDS ARE COOL. Alright, Madison, let’s get on with it now, get to the horses…

Inner Mongolia is the 3rd largest province in China. What used to be called “Outer Mongolia” is now just Mongolia. So, for clarity, Mongolia (Outer Mongolia) and Inner Mongolia used to be one nation, but for reasons of war and conflict and land disputes and politics (and the Qing Dynasty, and the year 1911, and World War II, and Joseph Stalin, and all sorts of other stuff that I don’t have time to go into because I spent three paragraphs on languages) there are now two separate sections: the independent country of Mongolia, and the Chinese province/autonomous region of Inner Mongolia.

Inner Mongolia stretches across much of the northern edge of China; the province borders Mongolia to the north, and, to the north east, shares a border with Russia just over 1,000 kilometers (620+ miles) long. I was heading up to 海拉尔 Hailar (Hǎilā’ěr), and then on to Hulunbuir, so I was about as close to Russia as you could possibly be. And OH BOY could you tell. We had one night to spend on our own in Hailar before joining the tour and heading out to the grassland, so I decided to splurge a bit on an older, austere, *very* Russian-feeling hotel room, and it was everything I could have hoped for.

The next morning (after what was, admittedly, a chaotic mess of trying to figure out where to go and what to do and who my contact was and what bus to get on and if I had a guide who spoke English or where my other tour mates were… I don’t think I’ll be traveling with this company again…) we drove out a few hours closer in to the grassland to meet our horses, practice a bit of riding, and prepare to head out the next day. Now, I’m in no way an expert horseback rider, I never took lessons or anything, but I’ve done quite a few trail rides and horseback safaris over the years and I really enjoy riding. For better or worse (and my answer is probably different from my mother’s answer), I have no fear on the back of a horse, so I was excited and ready to go.

I was paired with a horse named 白鼻梁 Bái Bí Liáng, or, White Nose Bridge. Right from the first day I got him, he was incredibly stubborn and did not want to stand with the other horses or go where everyone else was going, so, naturally, I loved him. With a lot of “加油, 白鼻梁, 加油! Jīayóu, Bái Bí Liáng, jīayóu! Come on, White Nose, you can do it!” we were finally able to come to an understanding and decide to cooperate for the next few days.

After our day of training, we hopped in a bunch of smaller vans and began driving in to the ᠬᠥᠯᠥᠨ ᠪᠤᠶᠢᠷ ᠬᠣᠲᠠ Хөлөнбуйр хот Hulunbuir Grassland 呼伦贝尔. Covering more than 100,000 square kilometers (39,000 square miles), Hulunbuir is recognized as one of the most famous grasslands in the world — with a natural grass coverage of about 80%, it truly is like looking out into an endless sea of green. Some believe that Hulunbuir is the birthplace of the legendary Genghis Khan.

The journey to get to our campsite was an especially interesting one because we had to drive right next to the border to Russia. No, quite literally. First we stopped for lunch in a small town and got a good look at where we were on a map (see video below) and then, as we got closer to our base, we drove along the edge of a small river – just on the other side was Russia. Our guides had us all put our phones in airplane mode for the remainder of the trip just in case our health code location tracking thought that we had been in Russia. That would certainly complicate things…

When we got to our campsite, all of the tents were set up and waiting for us. There were an assortment of two-person tents set up with air mattresses and sleeping bags, two big dining tents, and a few public “hang out” tents with carpets and pillows. My assigned roommate and I hurried off to stake our claims on the tent furthest out from the group, to try to enjoy the sounds of nature rather than people chatting. (Full disclosure: when I initially signed up for this trip, I was under the impression that we’d be carrying all of our tents and personal belongings on the horse with us, traveling along an extended path and setting up camp somewhere new each night. Rather, we had our tents set up in one home base and went out each day to ride different paths, always coming back to the same place each night. I can’t really complain, I still got to spend a week camping and riding a horse through the same grasslands that Genghis Khan did, so, all things considered, my life is pretty spectacular. But. I will be on the hunt for something a bit more like what I had originally hoped for.)

Our schedule was about the same for each day that we were out there. Wake up for a breakfast served in the dining tent, have an hour to chill and get the horses ready, hop on and go out riding for a few hours, come back to camp for lunch/nap time, go out riding for another few hours in the late afternoon, back to camp for dinner/drinks/socializing in the evening. My favorite part of every day was, unsurprisingly, the time we spent out on the horses. It can be so rare to go out into a part of nature where there is absolutely no evidence of human life anywhere even slightly near you, to feel like a small speck on this absolutely breathtaking planet of ours as you feel the sun on your skin and the wind blowing through your hair. We were blessed with some amazing weather — only had one rainstorm bad enough where we had to turn back — and so I got to spend hours upon hours out taking in this famous grassland.

As with most attractions, there is a romantic legend that accompanies this grassland:

Long ago, a beloved Mongolian couple was adored by their tribe. The woman, Hulun, was a beautiful and talented musician while the man, Buir, was a skilled hunter and horseback rider. They lived happy lives together in their glorious grassland home. One day, a demon came to the grassland, threatening their home and the safety of their tribe. After trying to fight it off together, Hulun realized that they would not be able to defeat the demon in combat alone. As the demon reached for her, she turned herself into a lake – sacrificing herself to drown the demon in her waters, saving her tribe and her homeland. Buir was heartbroken by the loss of Hulun, and so he dove deep into the lake to be with his love once more. A second lake appeared, and thus, the grassland was named after the Hulun Lake and the Buir Lake.

Of course, I’ve also read that “hulun” and “buir” simply mean “otter” and “male otter” due to the vast number of otters who used to make their homes in these lakes. So. Pick whichever story resonates more with you, I suppose. Or combine the two and spin a tale of star-crossed otters. (Do I sense a children’s book on the horizon?)

Hanging around the campsite at night was a nice way to get to meet some of the other people on the tour with me. There were only 4 of us foreigners on the trip, so we got to know each other pretty well, but we also spent quite a bit of time hanging out with some of the younger kids – they were excited to practice their English with us, and in return taught us some new childhood phrases to help us remember our Mandarin: “上, 北. 下, 南. 左, 西. 右, 东.” “Shàng, Běi. Xìa, Nán. Zuǒ, Xī. Yòu, Dōng.” “Up, North. Down, South. Left, West. Right, East.”

Our first night at camp was a full moon, and so one of the men on the tour brought all of his musical instruments to conduct a full moon sound bath meditation from one of the tents that evening, and invited anyone who was interested to join. I figured I may never get another chance to say that I took part in a sound bath meditation underneath a full moon out in the middle of the Hulunbuir Grasslands of Inner Mongolia with complete strangers, so, what the heck, might as well, right? I climbed into the tent around 9:30 pm to find the leader sitting with all of his equipment laid out around him. Though he spoke in Mongolian, one of the younger women was able to translate his instructions into English for me. We were asked to lie on our backs, get comfortable, and close our eyes. Then, for the next thirty minutes, he played us through his various gongs, chimes, wooden flutes, bells, and singing bowls, in what I imagine must be a specific order meant to help the process of meditation. Though I’m not the best at turning my brain off, I loved being able to release all of the tension in my body and feel as the various vibrations from the instruments resonated through me. Not a bad way to spend a night, eh?

As much as I loved getting to go out and ride every day, it was not without its, well, mind-numbing pain. For anyone who might not know, I struggle with hip issues; I’ve had hip pain since I was 16 years old, and had a double hip surgery (a bilateral hip femoral acetabular osteoplasty, to be exact) a few years ago to attempt to solve some of the problems. Long story short, my body really wishes my hobbies were not hiking mountains and throwing myself around upside down on metal poles and aerial hoops. So, suffice it to say, sitting in a saddle for a week was maybe not the nicest thing I’ve ever done for my body? Ah well. I couldn’t manage the meditation in the sound bath, but I got quite good at working towards just completely separating my mind from what was happening in my body during some of those rides. Worth it. Jīayóu, White Nose! Jīayóu, hips!!

On our last ride out before packing up and heading back into town the next day, we all brought our horses up to an open field to try something new: racing. Now I am a, shall we say, slightly competitive individual, so if I was going to race, I wanted to win. The only problem was that Bái Bí Liáng did not especially care for speed; on the rare occasion I or any of my guides could actually get him to canter or gallop, he would only keep it up for a few seconds and then decide he didn’t feel like it anymore. (Stubborn. Can’t imagine where he gets it from.) However, my roommate for the week – who, as it were, used to be a professional rider – had been paired with a rockstar horse who had no issue with speed, so she suggested that we try to switch horses for the race: I could take hers and get to experience a horse that would actually run, and she could try to coax a bit more speed out of White Nose. Game on. Y’all, I don’t know if you’ve ever been on a horse’s back as it bolts through an open grassland, but I’ve got to say… it’s rather thrilling. (And don’t worry, I won.)

Though my Hulunbuir trip wasn’t what I originally intentioned (and I still plan on doing that eventually), it was an incredibly fun experience and one that I will always treasure. At the end of the day, I ended up dirty, sweaty, and sore — the true markers of a good trip in my book.